Art History Week

The Renaissance is regarded as one of the most revolutionary periods in Western art history. Not since the ancient Greeks and Romans had such advancements been realized. Today, we’re going to look at three of them – one a rediscovered understanding and the other two new developments that completely changed painting in the Western world.

Contrapposto

The ancient conquerors, when they engulfed much of the known world, had a penchant for absorbing things from the cultures of the people they vanquished, including art styles and techniques. The Romans were so in love with Greek sculpture, they meticulously copied statues they admired and today we know many of the most famous Greek works only because the Roman copies survive. Like the famous ancient Egyptians, the ancient Greeks had developed a canon, or set of measurements, that they used to create their concept of idealized human forms. This is a fancy way of saying they used math equations to develop the measurements for what they thought was a perfect body; it’s enough to deserve its own article, but the main thing to know about it for our purposes is that it is the reason why both Greek and Egyptian art are so recognizable and consistent across their vast empires.

While Egyptian sculpture is characterized by stiff, almost abstract forms, the Greeks discovered a very important quality about the human body that made Grecian sculpture far more realistic: the way the human skeletal system carries weight. This characteristic is known as contrapposto and it refers to the way that weight-bearing limbs and joints appear to balance one another.

Being biped organisms, humans have two main weight-bearing limbs: the legs. You know that a person standing with their legs planted firmly on the ground and their arms hanging straight down at either side is a rather boring pose, right? It is very solid and stagnant. The major joints – shoulders and hips – are squared because they do not have to shift any weight when both feet are planted firmly on the ground. To walk or run, a human being must shift the weight of their body from one limb to the other, or from one leg to the other.

How often do you want to draw a person just standing there, doing nothing? And how often do you stand with your feet squared on the ground and your hands straight at your sides? I’m going to guess not often.

Lucky for us, the Greeks discovered that even though the joints appear squared off, or parallel, when a person is standing as described above, when a person starts to shift their weight, the joints either move toward each other or away from each other, depending on the movement or pose.

Let’s take an easy pose: slouching. Say a person is slouching against a wall; the wall structurally takes the place of a weight-bearing limb, leaving one leg with little to do, so all the weight is borne by the other leg, the wall, and one shoulder. Though it initially seems contrary to logic, for the weight-bearing leg, since it is doing so much work, the knee and hip will actually appear higher than the same joints on the non-bearing leg. This is because weight and gravity compact the human body (weight-bearing limbs will appear shorter), so when weight is absent, the body stretches out (so non-weight-bearing limbs will appear longer). Likewise, the shoulder that is holding the majority of weight against the wall is going to appear physically higher than the shoulder that is bearing no weight at all. To stay balanced, they create an invisible zigzag across the body.

If this is hard to picture, below is an example of a human depicted leaning against a stump. Note how the leg nearest the stump doesn't have to bear the body's weight, because the weight is shifted onto the stump via the arm leaning against it.

Now, compare that image, which is of a Roman copy of a Greek statue of Dionysus, with the Egyptian figures in the image below. Before scrolling down, look at the upper bodies alone; just from looking at them, what do you think the figures are doing? Now scroll further down and look at their feet.

Note how, even though walking requires shifting of weight, there is very little in the way of effect on how the rest of the body is carrying that weight.

That said, there is NOTHING WRONG with a more abstract/stylized art form; neither style is better than the other, they are simply different from each other! In fact, the Greeks and Romans admired and copied much from Egyptian art and culture, as well.

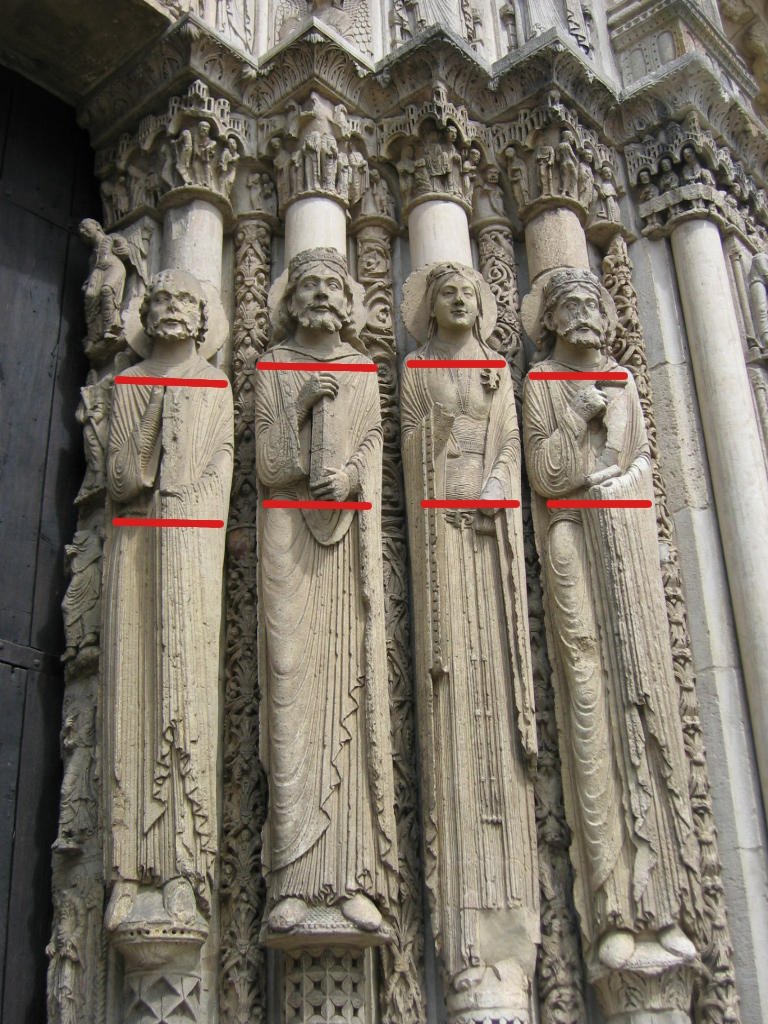

After the fall of Rome, the knowledge of contrapposto was largely forgotten in Europe for many centuries. Many medieval sculptures tended to look a lot more like the Egyptian sculptures in certain ways, and many medieval sculptors didn’t seem to understand how weight worked at all, with the feet positioned so that they appeared to somehow float on the surface of the bases:

They are actually very similar to Eastern-influenced, particularly Buddhist, sculptures -- but that’s another article!

During the Renaissance, contrapposto was rediscovered, and the most influential of Renaissance artists embraced this knowledge, and many applied it to media other than sculpture, although sometimes imperfectly. Also note that it's not just used in standing poses:

Sfumato + chiaroscuro

Two other things that revolutionized Renaissance art have almost as much to do with medium as they do technique. The main types of painting before the Renaissance were tempera (pigment is mixed with egg as a binder), encaustic (pigment is mixed with melted wax), watercolor (pigment is mixed with water-soluble medium) and fresco (water-soluble pigment is applied to wet plaster). During the Renaissance, a brand-new medium was developed: oil painting (pigment is mixed with oil and some kind of solvent, usually mineral spirits). Historian Giorgio Vasari, in his famous “Lives of the Artists” (1568), attributed the first use of oil paints to Dutch artist Jan van Eyck in the 1400s.

Naturally, new techniques were developed for the new medium; the translucent quality of oil paint now allowed layers of pigment to be built up and, because it is such a slow-drying paint, blended smoothly. Although the idea of shading had been around since ancient times, light source was not always understood. The refining of human observation during the Renaissance, and the development of the camera obscura (17th century Dutch painter Vermeer is believed to have used this device for his realistic paintings, but that is another article!), led to a better understanding of how light can be depicted: using shading with a defined, directional light source, called chiaroscuro, and sfumato, the softening and blending of colors and values.

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the early adopters of oil paint. His experiments with it were not always successful – those of you who know what happens when you mix oil and water can imagine what happened when da Vinci tried to create a fresco (applying pigment to wet plaster, remember) using oil paint. But he did demonstrate the beautifully lifelike look of shadows on skin by blending colors and values for smooth, seamless shading that emphasizes form in his other oil paintings. This technique, Sfumato, would go on to influence drawing and painting in the Western world from that point on.

Here’s a look at some pre-Renaissance paintings. Note the brush strokes that are very much like the hatching marks of pen and ink, and also note the “shading” tends to be large swatches of color and value, or emphasizing forms with little to no mind paid to light source:

Now here are some Renaissance and post-Renaissance oil paintings that demonstrate sfumato and a more realistic understanding of chiaroscuro, or shading with an established light source (note the shadows of the figures falling on the ground, other people and objects, for example):

Contrapposto, sfumato and chiaroscuro all influenced Western art from the Renaissance onward, even inspiring artists -- including the later impressionists, cubists and Pre-Raphaelites -- to try to break free of them. Still, their influence on art today remains indisputable.

* All artworks used in this article are in the public domain, as it has been more than 100 years since the original artists' deaths.

* All artworks used in this article are in the public domain, as it has been more than 100 years since the original artists' deaths.